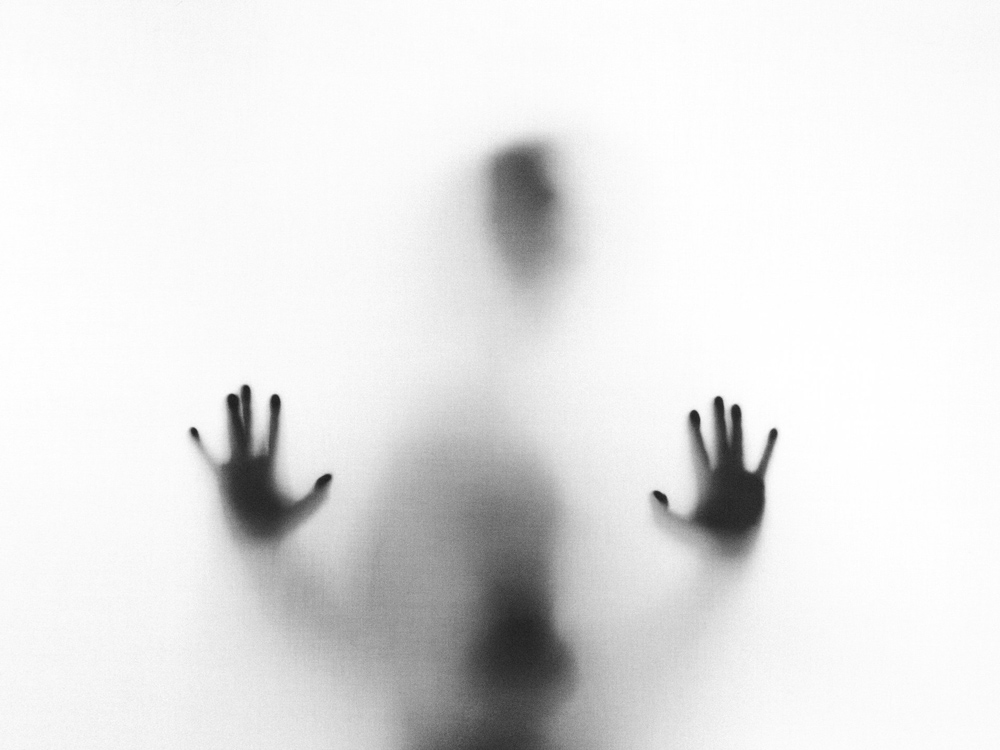

Do you know anyone who faces mental health struggles? Chances are, you do, as around 20% of adults in the United States live with a diagnosed mental illness or disorder. The total figure is likely to be much higher as many people are not diagnosed due to a number of factors which will be explored later. However, how many of these individuals diagnosed with mental health illness are outwardly violent?

How much of an impact does mental health play in the realm of crime?

The media plays a large part in the perpetuation of the idea that mental health issues and violence are intrinsically linked. A study conducted in 2017 found that over half of the study sample had an overtly negative tone whilst discussing individuals with mental health disorders. Moreover, just under 20% of the sample studied directly associated mental health disorders with violence. Unfortunately, even in TV series that have been widely praised for their mental health representation, there seems to be an underlying perpetuation of damaging stigmas surrounding these individuals. (Farrel, 2018)

The assumed link between mental health and crime is often overstated, as data from scientific studies often focuses on high-risk individuals such as those already incarcerated or in-patients. Therefore, studies are not representative of society, as there are many individuals in our communities who struggle with their mental health. So, even scientifically speaking, we have a poor and inaccurate portrayal of mental health and its link to crime and violence.

But there is a link, a clear one.

- 95% of young people aged 16-20 in youth offending institutions have at least one mental health disorder.

- 45% of children who have conduct disorders in the United Kingdom, go on to commit over half of all crimes.

So, there is a problem, and it is only getting worse. So, where are we going wrong?

According to Sarah Brennan, the chief executive of Young Minds Charity, this is because of progressive local authority cuts. The system which used to accommodate so-called ‘step up, step down’ treatments or Tier 1 supplied locally by councils, has been completely decimated due to these recent funding cuts. Instead, teens must be referred to CAMHS (a Tier 1, ‘Universal System’), an already overburdened system. This is a fixed system which focuses heavily on the diagnostic side of mental health. If you need further help after the diagnosis then there are options: in-patient care, crisis care, and urgent care teams. But when you are out of these well-structured systems, where do you go? With the slow demise of Tier 2 structures, there is no clear pathway. Furthermore, Tier 3 services are difficult to access, so the more complex and challenging cases are being dealt with by the under-funded Tier 2 systems. This creates a greater backlog, further perpetuated by the increase of children becoming mentally ill who need to go straight to inpatient care. In these crises, children are then hauled all over the country. So, the inpatient/crisis facilities are dealing with children from out of the ‘catchment’ area. Not only does this strain the system further, but it also deeply affects the patients, as they are cut off from their community, friends, and other support networks.

We are faced with the question of responsibility. Whose responsibility is it to make sure these young offenders are being supported by the local services? Why should such vulnerable children be forced to wait at least 6 months to be seen by CAMHS? A task force, put together in 2015, focused on trying to understand the one factor tying all these young offenders together. Some disagreed with this approach, arguing that it hides the complexities of each individual, but by underpinning a commonality between this group, it highlighted what needs to be done to help all of them.

What similarity did they find?

Trauma

The 2015 task force defined trauma as events which had an impact on the child’s development; this included both neurological and emotional disruptions. In scenarios in which children are referred to other systems, children are not treated as individuals who have experienced trauma, but are instead labelled as having behavioural issues. Therefore, the underlying, root cause of the ‘issue’ is not addressed or improved.

Another reason this is happening is because of CAMHS’ system. Children who do not present with symptoms of PTSD/c-PTSD cannot be diagnosed as they do not have a ‘classic’ mental health disorder. Therefore, CAMHS has no clear pathway of care to put them on, and instead will focus on the presenting ‘issues’ (often behavioural) and will put the children onto anger-management or medications for ADHD. This is where local and community services step in, people with an in-depth knowledge of the area and the children. These cases are complex and often need more than a medical lens. These children are being failed by this uncoordinated system and may, therefore, go on to develop other mental health problems. If these children are guided through traumatic experiences and situations early into their entry into the mental health system, they are increasingly likely to improve their conditions.

To even begin to figure out where this precious responsibility lies, there needs to be a shift in the way these services communicate. As of now, CAMHS, AMHS and social care are separate identities, and this is at the crux of the problem. There is an ingrained paranoia surrounding sharing information in the medical profession. Perhaps rethinking our approach to data protection should be one of our priorities. Confidentiality is of the utmost importance but sharing information can save lives and help young offenders when released from prison.

Photo by Stefano Pollio on Unsplash